WATERWAYS IN THE BAY

Duane K. McCullough

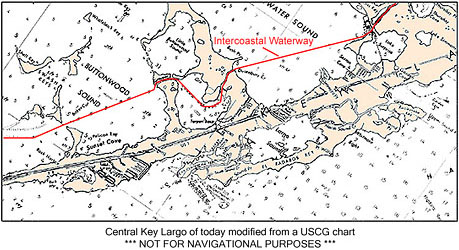

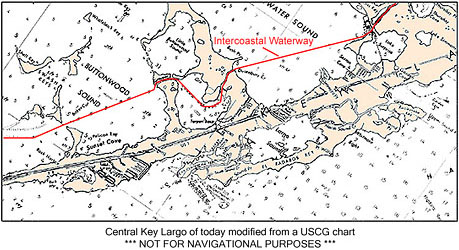

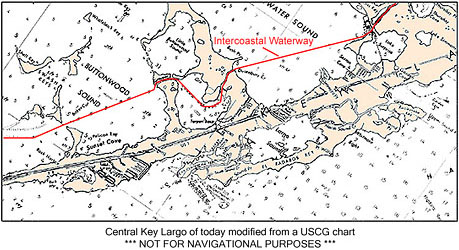

Image of nautical chart of Key Largo area

We are now entering Grouper Creek that links Tarpon Basin with the Buttonwood and Little Buttonwood Sounds. Grouper Creek was made wider than it originally was over seventy years ago during the blasting and dredging activity of the Inter-coastal Waterway canal project.

Completed just before World War 2, the Inter-coastal Waterway canal project changed the hydrological makeup in upper Florida Bay when it allowed fresh rainwater to leak out the local lagoons and be replaced with salty seawater from both Florida Bay and other saltwater sound areas north of Key Largo.

However, the hydrology of the area has also been changed by other man-made canals projects -- such as, in the early sixties, a canal was cut across the middle of Key Largo from Blackwater Sound to Largo Sound so that pleasure boats would have a short cut from the bayside to the Oceanside waters of what is now John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park. This event allowed even more freshwater of the area to be replaced by seawater.

Also in the early sixties, man-made canal projects just north of upper Florida Bay on the mainland were created as drainage canals to protect agricultural interest and also to serve as a commercial waterway to a rocket engine building factory that never materialized. These canal projects have resulted in the redirection and untimely redistribution of the natural seasonal surface water flow from the Everglades aquifer to upper Florida Bay.

Recent efforts to correct the nearby canal projects on the mainland seem to be in the works, but any attempt to restore the upper Florida Bay realm to the way it was before the Inter-coastal Waterway was constructed will be met with great resistance from those who enjoy the use of the waterway with their large boats.

Even if the Inter-coastal Waterway were to be abandoned somehow and the lagoon areas of Key Largo were restored to the freshwater estuary that it once was, the danger of freshwater pathogens from storm water runoff and septic systems near and within many man-made canals in the area would pose a major health problem. As it is now, the natural chlorine within seawater is neutralizing the threat to some degree.

Moreover, seasonal wind and storm tides provide some flushing opportunities of the accumulated nutrients from human activity out to open water byway of these canal waterway projects.

Of great concern to some hydrologist in the area is how the concept of deep injections sewer wells used by large business facilities may be collectively contaminating the freshwater areas that lie beneath the island of Key Largo with “treated wastewater”. Most all large islands in the Florida Keys have a freshwater zone or “freshwater lens” lying underneath them wherein fresh rainwater floats on top of the surrounding saltwater.

For example, it has been recently estimated that the volume of the natural freshwater lens that lies beneath the island of Key West in the wet season equals the volume of freshwater that is pumped out of the ground in just two days from the mainland well near Florida City. If the hidden freshwater area under Key Largo gets saturated with too much “treated wastewater” from these deep injection sewer wells, the health of the greater ecosystem could suffer.

Perhaps someday in the future, the Inter-coastal waterway channel will be made obsolete when better aeronautical technology invents efficient flying boats that would not need to use it . And perhaps better water collection and recycling technology will provide the inhabitants of Key Largo with clean freshwater to use without taking so much from the Everglades aquifer.

Now with some understanding of the natural and unnatural layout of the area, let’s go visit the bayside of Key Largo and see how the modern day human wildlife lives.

<< Previous Page BUGS IN THE BAY <|> Next Page MODERN HUMAN WILDLIFE >>

Return to the Islands of the Bay Coverpage

Return to the Lost Fountain website